Critical theory appears to be on the wane within the practice and discourse of art, architecture and design. This may be attributed to the increasing commodification of contemporary art and “starchitecture” throughout the Reagan-Bush era, ongoing reactionary attacks on left or centrist ideas, and/or the gradual acceptance of a “post-critical” relativism among practitioners and scholars alike. At the same time, a self-criticism from within the left itself questioned the authority, sponsorship and objectivity of neomarxist scholars and artists, the possible fetishism of their antifetishism, as well as the lack of responsibility/vision once the unvarnished truth strips the world to a shell. As the world now shifts into a permanent state of economic and environmental emergency, critical theory appears unequipped. And yet, just as power, through every age, requires art and high design to adorn and legitimate its hegemony, the case for truth, compassion, and solidarity with the marginalized cannot be neglected. Based on an evaluation of Francis of Assisi’s critical-poetic design practice within the political/religious milieu of premodern Italy, a set of strategies will be proposed in this paper for architects and designers here, on the other side of modernity.

[click any image for caption and gallery]

What is the current state of critical theory in design? Mark Jarzombek, Director of MIT’s History and Theory of Architecture program, believes that in architecture, at least, its voice is marginal if not dead.[1] Foucault, Benjamin, Adorno, Delueze and Derrida continue to populate the reading lists for architecture students alongside Tafuri, Eisenman, and K. Michael Hays. However, Jarzombek believes that after Tafuri, most architectural thinkers wrote less in the service to social justice, feminism, or anti-globalization than to serve as a scholarly-sounding veneer for what is otherwise capitalist avant-garde design. Revivals of Bauhaus modernism, Russian constructivism and, more recently, seventies bubble-futurism has driven recent architectural fashion. Where critical theory helped shape a few significant projects in the late 20th c., such as Samuel Mockbee’s Rural Studio, Aldo Rossi’s cemetery-cities, Eisenman and Tschumi’s contributions to Parc de la Villette, or Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin, its discourse throughout the profession has largely been discarded for an unapologetic embrace of computational wizardry to churn out green-washed, media-soaked fetish objects on a vast scale.

Witness contemporary Dubai, Shanghai, or any of the recent Olympics. Perhaps all this is to be expected given how expensive architecture is as an art form, including having to negotiate often unprogressive urban regulations, building and ethics codes, client needs, an often unscrupulous construction industry, media campaigns and tight deadlines. As in a Hollywood blockbuster, the credit list for architecture could run for hours, but unlike film, there is little opportunity for on-the-fly, radical low-budget creation. There are just too many people that need to sign off on a public built work.

Architecture, however, is not the only medium through which critical theory, radical or neomarxist thought has been largely unrealized. Hal Foster, Fredrick Jameson and others admit that commodification continues to smother contemporary art and design production from the outset.[2] Given that Marx himself believed that capitalism was not to be demolished but surpassed, then cultural producers are now advised to work critically within capital to create what Adorno would term “authentic” works unmotivated by self-promotion or profit.[3] Indeed, Jameson has given the left much hope in his call to augment capitalist critique with the need to explore utopian visioning at the core of early Marxism. Resisting oppression or ironically allegorizing commodification is not enough; better worlds need to be proposed. Indeed, the argument is similar to the conclusion arrived at by Elaine Scarry in her book, The Body in Pain.[4] To the degree that pain incarcerates a body or, by extension, an oppressed society, is the degree to which imagination needs to be activated as an anecdote for release.

Now, if one accepts Jameson’s utopian proposition, then the significant work done by philosophers Paul Ricoeur, Gianni Vattimo, Richard Kearney and Edward Casey on the phenomenological/hermeneutic imagination might provide a map for a “critical poetics” which can simultaneously resist hegemony while proposing “world’s otherwise”. Within architecture this approach might best be exemplified by selected works of Le Corbusier and Steven Holl, Peter Zumthor, and the masques of John Hedjuk.

But can contemporary phenomenology, as a design practice, escape the complicity of its founder Martin Heidegger with totalitarianism, as we see with Le Corbusier during the French occupation, or commodity-capitalism in the case of Holl and Zumthor’s recent works? Time will judge the social effects of any truly subversive critical/poetic design practice working from within an oppressive structure. Commitment and persistence to justice over a lifetime should probably be the only cause for personal praise. Evading fame, power, envy and capital to remain fully fixed on social transformation only increases the burden of the engaged designer. Early works of strength and poetry can rapidly devolve into a pathetic pastiche for profit as a career unfolds. But, how to remain focused? I want to offer one, albeit brief example of a designer’s oeuvre that might map an approach for the contemporary demands of a critical/utopian practice.

Born in 1181, St. Francis of Assisi achieved a level of fame in his own lifetime that was extraordinary by any standard. By the time of his death in 1226 he had over 5000 vowed followers wearing the same habit he designed and wore, singing the canticles and prayers he composed, and living in the architecture he designed. Since the relics of saints were among of the most valuable commodities in medieval Europe, his corpse was so prized by his native Assisi that the town assigned six guards to accompany Francis during the final months of his life. If Assisi’s rivals such as Perugia stole his freshly dead body, they could build a basilica, attract pilgrims and boost their economy for centuries. Indeed, in his later years people were snipping off portions of his habit for relics while he preached. As a result, Francis was well aware of the impending commodification of his memory and remains, and chose very carefully how to bequeath them to Christendom.

In a time of new artisan trade and mobility within Europe, Francis stood out as an allegory for their ideas, beliefs and struggles. During his youth in Assisi, the town overthrew its German military occupier to form its own commune. As a young man he lead a local troubadour troupe and worked in the medieval fashion industry, travelling to France and importing fine French textiles for sale in the family shop.

After a near-fatal illness caused by being a prisoner of war in neighboring Perugia, Francis began to question his social status, and, to the horror of his family, started to give their luxury items to the poor as he himself experimented with living among them. He was trying out what would become a lifelong project: to reverse the order of his sensual experience so that all that what was formerly “sweet to him would be experienced as bitter”, and vice versa.[5] This led to one of his earliest performances when his father took him to court in 1204 to sue for his inheritance (before Francis could give it all away). Francis not only conceded his loss, but before the entire town he removed all his clothes and, standing naked in the town square, gave those to his father as well. Events such as this were, arguably, the foundation of his fame. He might best be understood less as another poor, wandering preacher of the Middle Ages than the father of multimedia performance art. For Francis, the former cloth merchant, this began with the design of his outfit.

He wanted to imitate a Jesus that was believed, due to a local misinterpretation of some scriptural passages, to be a poor, wandering leper. Leprosy was a European pandemic at the time. There were four leper colonies near Assisi, so Francis moved into one and eventually designed his own habit in partial imitation of leper garb: cheap undyed sackcloth, loosely worn with a rope belt. The recently carbon-dated tunic in the church of S. Francesco in Cortona seems to have been his, and appears in an unmistakable T-shape, as eyewitness accounts from the time verify.[6] This was probably reinforced by Francis’s preferred prayer position with arms outstretched to the side, or as was once recorded, lying face down on the dirt floor of his mud and stick hut, arms out in a T-position and two candles burning above each arm.

The T or tau was well known as last letter of the archaic Greek and Hebrew alphabets. “The tau symbol, had, above all others, his preference,” says his contemporary Thomas of Celano. “He utilized it as a signature for his letters and he painted a drawing of it on the walls of all the cells.”[7] The symbol of the tau has a lengthy and complex biblical history as the purported sign and talisman used by Moses and Aaron, and, of course as the cross Jesus was crucified on.

Often living, at first, in abandoned caves, pits, tombs and ovens, Francis appeared in this outfit as a “homo selviticus” or wild man. On his preaching tours, walking barefoot from town to town, his habit became a key prop. Often it was removed so he could demonstrate his naked poverty, or have his brothers lead him away naked, in ropes, like a criminal for his sins. In one sermon for the nuns at San Damiano, Celano tells us that he entered, silently knelt, made a circle of ashes around himself, sprinkled some on his head, recited a penitential psalm, then left. These “symbolic sermons,” as Celano called them, “made a tongue of his whole body.” And the result was not only performative but participatory: all present were reportedly moved to tears, prayer and penance. Indeed, Francis likened himself to the way painted icons were utilized as memory devices at the time. Deploying himself as an icon, his performances included preaching to birds, talking wolfs out of threatening the towns, preaching peace to the crusader’s enemy, Sultan Malik-al-Kamil, and creating the first midnight Christmas crèche in a cave at Gubbio, complete with a manger, hay, live animals, townspeople as actors, and Francis preaching using the curious intonation of a humble lamb, according to eyewitnesses.

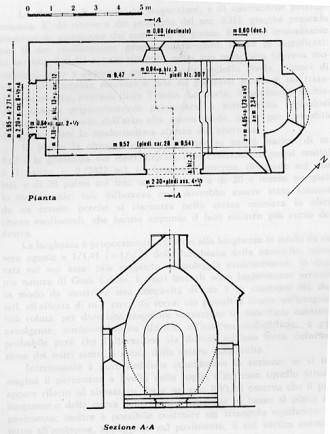

A problem then arose. As his vowed followers grew in number they needed to be housed, forcing Francis to think carefully of how to dwell in imitation of a poor Jesus. After a number of experiments in dwelling, Francis came upon a tiny, abandoned chapel in an oak forest that he renovated himself in 1205-06 by begging for stones from locals. Around this chapel, called St. Mary of the Portiuncula (or the little portion) he and a dozen or so of his earliest brothers dwelled in mud and stick huts and had a garden in which Francis insisted that vegetables, flowers and weeds would grow together. Silence would reign within the hedge-bound friary, except, as Francis specified, for occasional exhaltant bursts of joy. In 1216 European pilgrimage routes changed to include the Portiuncula because Francis obtained a unique papal indulgence for the forgiveness of any mortal sin, like murder, upon its pilgrim-visitors.

For Francis, the Portiuncula compound acted as a template for all future architectural construction for the order; reports from Italy to Germany to England of friars living in mud and stick huts and praying in borrowed tiny chapels no bigger than the Portiuncula continued until his death. However, opposition to these poverty restrictions, which included his prohibitions on ownership of books and the touching of money, grew louder as his order began to attract scholars, clerics and wealthier followers. When Francis returned to the Portiuncula after one preaching tour, he found a new stone and tile building there to house the friars. Francis leapt onto the roof and, before his brothers, demonstrated his displeasure by tearing it down by hand.[8]

However, as the papacy began to support–against Francis’ wishes–the order’s moderation and clericalization, Francis quit in 1219 as the Minister General of the order he himself founded. In his final seven years, he nevertheless redoubled his efforts in preaching/performance tours to convince all people to reverse their sensual preference for the bitter over the sweet, culminating in his careful and lengthy preparations for his death. He designated the Portiuncula as the place he wanted to die naked on the bare earth, and even had a dress rehearsal, or should I say undress rehearsal, a few days before. Dying naked was important because that would reveal for the first time his stigmata–the five holes in his hands, feet and sides which, although verified by independent witnesses, were probably the result of a holy self-mutilation. Canticles, food, candles, shrouds and a head pillow were all prepared to his specifications. Although he was not a priest he performed a mass that he designed, bestowed blessings on his successors, and, most importantly, delivered his final Testament, which he drafted and edited months beforehand.

Here, in this extraordinary tableau or performative icon, Francis reinforced his architectural vision: that his brothers should dwell as “pilgrims and strangers” and resist ownership of churches and buildings.[9] This section is prefaced by a quote from the Acts of the Apostles which he applied to himself: “And I worked with my hands”, claiming that all his brothers should do honest work, even if not paid. This was in direct confrontation with the order’s new direction to be scholarly, monastic and priestly, living off donations, and thus not needing to “work” like real lay people did. Resisting building and book ownership, refusing to own the tools of their trades, or take on any authority or leadership roles in the workplace were all intended on making his order into permanent day laborers, apprentices and journeyman, with no food stored up for the next day, as per Jesus’ words. This was the vita of the early order which continued, in various Franciscan communities, at least twenty years after his death. The Testament gave those workers hope.

Previously, such utopian social visions were only found in monastic and hermit groups, walled off from the world, or among some of the heretic groups like the Cathars operating in Europe at the time. They all knew that there was something intrinsically good for the human spirit about non-profit work, in particular hand-work, done in service to–and not to have authority over–a community. The Franciscans were among the first Catholic monks-in-the-world, and contemplatives-in-action. Their mendicant itinerancy, having nothing for the next day, ensured a daily encounter with their mortality, dependence on a benevolent cosmic order, and the practice of gratitude. It is hard not to think of these values as consistent with the best of contemporary Marxist or socialist ideals, and providing an example of personal commodity resistance for the long-haul.

As designers or architects interested in seeing the best of critical theory shape our practice, we might do well to focus, as the early Franciscans did, less on the product and more on the process of production. In this way the Occupy movement was not far off the mark as an art form that embraced critical theory. Their hand-built, low-tech, leaderless tent-cities, their chants, puppetry, noise-makers, signage and clothing, were performative vehicles for a greater idea, not necessarily products in themselves to be sold to raise money for the cause. Persistence in their ideas may only come about through a combination of integrated grass-roots organizations combined with personal daily contemplative practices to keep it humble, reduce self-centeredness, resist branding, and to learn about the elders and prophets who walked the same path. This personal practice is just as important as the social practice, and without self-discipline (what Francis called penance), the Occupy movement will likely go the way of their hippy parents who largely transformed into yuppies.

As for the product, consider the examples of Francis’ Tau outfit or the Portiuncula. They were open-source designs of recycled, simple materials which were hand-worked, non-specialist and easily repaired. Most importantly, however, their designs utilized metaphor over allegory, opting for the thick symbolism of poetics rather than a single-message one-liner of a jester (such as Warhol, Hirst or Koons). Just as the Tau transforms the wearer into a crucifix, or a healing Hebrew talisman, or an apocalyptic sign or final letter of a sacred alphabet, so did the Portiuncula, with its hand-built, starry vault carve out a little portion of heaven in the silent joy of the penitential wilderness: the womb of Mary’s Annunciation and the cave-tomb of her son’s death and resurrection. Well-deployed metaphor ensures historical resonance, and invites participation. If contemporary critical designers have focused too much on the product over the production to realize their success, neo-Marxists as a whole might be focused too much on the system over the symbol. Without poetics in design can solidarity with the marginalized persist for the long-haul against adversity, right-wing opposition or capitalist commodification?

-

1. “The State of Theory” in Architecture and Theory: Production and Reflection, Luise King editor. (Hamburg, Germany: Junius Verlag, 2009): 262-273 (262).

-

2. Hal Foster, “Post-Critical,” October (Winter 2012): No. 139: 3–8; Fredric Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future. The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, London (Verso, 2005).

-

3. See “Capital as a Revolutionary, but Limited Force” in Karl Marx, The Grundrisse (New York: Harper & Row, 1971), 94-95.

-

4. Oxford University Press, 1985.

-

5. 2 Cel 9.

-

6. La Provincia Toscana dei Francescani Minori Conventuali, L’eredità del Padre. Le reliquie di s. Francesco a Cortona a cura di S. Allegria e S. Gatta (Padova: Edizioni Messaggero, 2007).

-

7. 3 Cel 3; 3 Cel 159.

-

8. 2 Cel 57.

-

9. Test, 24; LR 6.

A version of this paper was presented at the University Arts Association of Canada Conference, Montreal, 2012.