Menlo Park is an online journal about the collision-zone of art, design and human-made space. Some current practice attempts to define a relevant criticality interleaving the fields of contemporary art, design and landscape/building architecture. Has the criticality of the avant-garde been eclipsed by a notion of design that is a pure reflection of the dynamic of techno-culture? Has design been relegated to the role of aesthetic adjunct to a culture of engineering and technology (its interface designer)? Perhaps this problematic can lead us to explore the possibility of a new criticality that asserts a reformulated mode of inquiry that makes its place not in the hermetic world of art but rather inhabits, however strangely, the world of everyday or ‘applied’ making? This is a provocative debate that traverses academic and practice-based discourses. Menlo Park is a venue for this conversation.

Menlo Park takes its name from Thomas Edison’s research and manufacturing facility in New Jersey (1876-87). The original Menlo Park served as the prototype for the high-tech campus/R&D facility of today (the Lab). Likewise, Edison was the archetype inventor/ designer/entrepreneur. Needless to say, naming this online journal after Menlo Park is a playful provocation. Menlo Park is a venue for discussing the things that techno-culture has forgotten by engaging in a rigorous conversation about the future of the ‘complex’ that is the relationship between art, design and technology. Contemporary art and design share historical roots in the avant-garde but have become estranged cousins whose differences have calcified around an antiquated discourse of ‘pure & applied’ arts. Menlo Park asks artists and designers alike to put some pressure on this institutional division and to conjecture what criticality could mean in relation to contemporary making, building and planning. (af)

Menlo Park

ISSN 2291-3165

(first issue, vol. 1 no. 1: March 2013)

Andrew Forster, editor

Anja Bock, managing editor

Menlo Park is a free online journal. You can subscribe to receive email updates. Send us you email for occasional news and regular new issue details.

SUBSCRIBE HERE

COPYRIGHT

Content and presentation copyright Menlo Park online journal and the authors. Authors retain copyright for articles and have granted Menlo Park right of first publication (unless indicated otherwise in the article notes) with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY-NC-ND) allowing distribution and citation of the work with an acknowledgement of the work’s authorship and initial publication in this journal.

All image copyright is retained by the rights-holder. Whenever possible this information or Creative Commons permissions are contained in an image file’s meta-data (following IPTC standards). Use of copyright images and images with no apparent copyright on this site is governed by the terms of ‘fair use’ for purposes such as criticism, comment or scholarship, not intended for commercial purposes.

CITATION

Articles, PDF’s, and documentation, unless otherwise noted, are copyright of the authors with Menlo Park online journal as first site of publication. Citation of articles from the site or downloaded as PDF should contain a reference to the author, Menlo Park online journal and date of publication (found at the head of each article).

PUBLICATION & CONTACT

ISSN 2291-3165

(first issue, vol. 1 no. 1: March 2013)

address: 4624 de l’Esplanade, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2T2Y5

general email: edison@menlopark.ca

for submissions contact see ‘submissions’ link under ‘about’

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Design and production of the first issue of Menlo Park was funded in part by a CUPFA PD grant (Concordia University, Montreal).

Web site implementation by Phil Jones.

Since we seek a conversation that crosses boundaries of various practices and fields, Menlo Park is not a journal following a strict academic model. Articles and reviews are shorter and discussion is encouraged. There is an editorial selection committee and a peer review process to ensure that contributions are focused and rigorous. Submissions of abstracts and articles are encouraged. Please submit a 300 word abstract and draft article HERE. Submissions are reviewed twice a year (deadlines: June 1, November 1).

Menlo Park is an independent no-profit journal. Making a contribution will help Menlo Park to continue thinking.

Fill out the form below to receive notification of new issues. Subscription is free. Your email is confidential and will be used exclusively for Menlo Park related news.

Last Room begins as an ideas competition which asks designers, artists, architects and writers to imagine a last room – only possibly a room for dying but certainly a room for living. Is this practical design for use or a conjectural/philosophical inquiry? Is this a call for practical alternatives to institutional architectures geared to efficient and cost-effective care? Or is it a call for a philosophical meditation on how we (consciously and unconsciously) ‘build’ the room as the world around us, where the last room is analogous to the first room we invent to contain the infinite universe outside our body—the first inside that is outside?

The Social Studio is a fashion label, café and social enterprise in Melbourne, Australia. Design is a vehicle to generate education and employment opportunities for young people with talent from refugee backgrounds. A retail shop sells beautifully crafted products made in-house and promotes sustainable and ethical fashion. Events and workshops … Continue reading →

How can theorizing one’s practice bear on the task of critical thinking? We have artists who are now graduating from doctoral programs. We know that many of these artists are extremely competent. They know their aesthetic theory. They know their art history. Many of them know complex technological processes. And many of them already produce engaged and occasionally exciting works. What more can one want from an educational program? Is there any serious problem here? The answer is yes...

While commercial appropriations are taken for granted in fashion and design, the field of visual art has always maintained at least a pretext of critical distance, if only in the guise of artistic freedom. Critical distance, in a contemporary context, is a matter of thinking critically about the convoluted culture that both artists and designers are currently implicated in, of harnessing the conceptual possibilities of creative practice without directing it toward a commercial outcome.Takashi Murakami’s artwork throws open this critical door and launches straight into the heart of commerce.

Morality and the pursuit of authenticity have been of perennial concern to the practice of form-giving — specifically design. To design is to mark out; it involves separating out what is from what should be. Inherent in this process is the establishment of a need. Victor Papanek, for example, posits that “design is the conscious effort to impose meaningful order.” Whether this is the ordering of shapes and lines on a sheet of paper or the gathering of materials to create a tool, the designer engages in a quasi-rational process of selecting a goal and a means of achieving that goal.

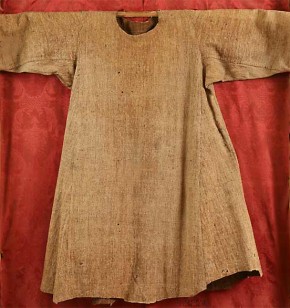

And yet, just as power, through every age, requires art and high design to adorn and legitimate its hegemony, the case for truth, compassion, and solidarity with the marginalized cannot be neglected. Based on an evaluation of Francis of Assisi's critical-poetic design practice within the political/religious milieu of premodern Italy, a set of strategies will be proposed in this paper for architects and designers here, on the other side of modernity.

REVIEW

Perhaps what is needed, following Hal Foster’s denunciations of design as mere consumerist manipulation in the service of greater efficiencies for capitalism, is recognition of a more general outline. That would be one that attributes the root of the problem more deeply in a description of the rationalist prejudices that dominate our thinking and being. For the style of critique demonstrated by Foster and his colleagues this would be bad news, leaving them revealed as a part of the problem in so far as their project is itself inextricably dedicated to the founding of criticality in a modernity already itself a practice of instrumental rationality.

INTERVIEW: VITO ACCONCI

What started in the 80’s was when I talk about stuff I used to say ‘I’ and then I had to start saying ‘we’ because it’s a group of people working together... The group has changed over the years but ‘we’ became important because when I thought I was doing architecture I started to think I have to work with other people, because I don’t think architecture can come from a single viewpoint. It has to come from a group of people thinking together, talking together and especially arguing together. I think this condition is important. I want architecture to have loose ends, because if it doesn't I don't know why anyone else would want to be there.